The Burning of Allan Wikman

Remembering a modern-day incarnation of Don Quixote who waged hopeless battle against everything that sucks

It’s a quiet October night in 2007 on the shore of the Hudson River in the northern reaches of Poughkeepsie. Waves lap gently against a floating dock populated by three antique wooden sailboats. A miniature village of pup tents is clustered in the lee of the Cornell Boathouse on the Marist College riverfront, each one enveloping a sleeping soldier in Revolutionary War garb. The group is camping for the night in anticipation of their last leg of a 53-mile human- and sail-powered journey up the river from Verplanck to Kingston, where they will join in the misguided annual “celebration” and re-enactment of the pointless and cruel torching of that city by retreating British forces in 1777. The scent of roasted meat lingers in the frost-tinged air. No one notices a dark figure lurking at the edge of the encampment, snapping flash photographs of the sleeping re-enactors.

A few hours later the quietude is ruptured by a loud cry: “Hey, asshole! What do you think you’re doing?” One of the vintage craft, the 25-foot-long DeSager, is being pulled away from the dock, swiped by what is thought to be a pair of pirates, who can be heard paddling furiously offshore in a work boat, slipping out of sight in the murky gloom. The sentinel, Chris, with an adrenaline boost jump-starting him from what was a deep slumber, decides against leaping into the DeSager, which is still in range of the dock; he doesn’t really know how many of them there are, or if they are armed. The rudely awakened campers check the remaining two boats, upon one of which, before he had risen with a full bladder for a midnight pee, Chris had failed to notice a tall man standing a few minutes earlier, fumbling with a tough knot. Someone reaches in his floppy leather pack, pulls out his cell phone, dials 911.

A crew jumps into one of the remaining boats, the Cod Peace, and rows out into the river in hot pursuit. Another re-enactor grabs a large stick and starts running southward along the river’s edge, peering after the marauders and hoping to catch them coming ashore. He notices the Cod Peace gaining on the thieves before losing sight of the chase. The pirates, apparently fearing capture, set the DeSager adrift in the middle of the river. The crew recovers the craft and returns to camp as the pirates slip southward into the night.

Meanwhile the police arrive, sirens screaming, lights ablaze. The encampment is in an uproar. The gall! The indignity! It’s an unusual call, to say the least.

The re-enactors eventually go back to sleep, although this time with an alert sentry posted. Waking up to what they think is a rain deluge but is actually the college’s automatic sprinkler system giving them a dousing, they sail/paddle to Kingston the next morning, cursing the name of Marist but arriving on time to join in the British attack on the beach. A police report is filed and forgotten. Sixteen years later, the foiled crime remains unsolved, and the mysterious pirate force is still at large.

The candidate

In this tiresome American political environment, with knee-jerk Red vs. Blue teams perennially trying to decide between the nation’s two force-fed ideologies by means of another flawed pair of anthropomorphic cartoon caricatures foisted upon the electorate as presidential “candidates,” and with powerful incumbents from both major parties destined to preserve the status quo on the congressional and state levels against weak competition, it’s comforting to imagine a time during which there could have been a mythical Third Way bubbling up into the zeitgeist. Indeed, back in 2008, one relatively obscure local race in the Hudson Valley stood out as a genuine story: a three-way tilt for the right to become the first ever executive of Ulster County, which in 2006 had approved a fresh new charter creating that form of government.

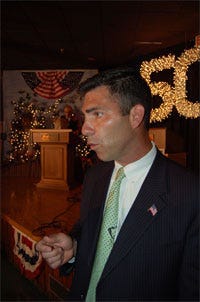

The obvious shoo-in at the time was the recently minted Democrat Mike Hein. A telegenic smiley guy, he was the virtual incumbent by reason of his position as the county administrator and his anointing by the region’s hydra-like bipartisan power structure. But he had some remarkably interesting competition. The Republican entry in the race was Len Bernardo, a likable and reasonable-sounding skating rink owner, Independence Party member and proponent of green technology.

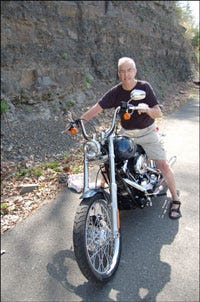

Even more interesting was the big, unpredictable fly in the ointment: Allan Wikman, a tall, gaunt septuagenarian who lived alone in an apartment on the fourth floor of a senior public housing tower, subsisting on a $1,169-a-month Social Security retirement check. He took medication to ward off depression, which didn’t prevent him from maintaining a surprisingly wide variety of acquaintances and friendships that he nurtured by making daily rounds of his adopted town of Kingston, N.Y. on foot or on a bicycle, 12 months a year. While his carbon footprint was as close to zero as a white man in America could hope to attain at the time, his ambition was boundless. Wikman was one of those figures who have plagued local municipal boards and legislatures across the land since before the British were driven from these shores; he was a political gadfly of the worst – or best – sort, depending on your point of view.

A former actor and Madison Avenue idea man with a passing physical resemblance to – take your pick – either Jimmy Stewart or Franklin Delano Roosevelt (whom he played in a traveling show of “Annie,” despite the fact that he disdained pretty much everything the man stood for), Wikman made his “Madmen”-esque mark with multimillion-dollar campaigns for Colgate-Palmolive and other corporate giants in the time before his nervous breakdown brought him low. A proudly iconoclastic figure, he was prone to long-winded and sometimes baffling public pontifications, either in a stentorian oratorical style reminiscent of a 1950s newsreel, or in rambling, oddly punctuated e-mail missives, taking on the powers that be regarding such matters as taxes, budgeting, corruption, incompetence and governmental reform. In his elliptical, dyslexia-influenced way, he often made enough sense to be taken seriously. He ran speaking seminars, lobbied successfully for public school music programs, performed literary readings, and engaged in vigorous e-mail campaigns to publicize the many issues that intrigued his active mind.

Cleaning up, just to get mud on your face

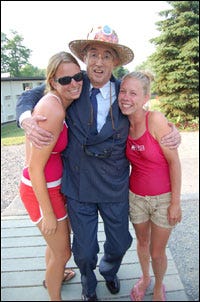

In running his insurgent populist campaign for Ulster County’s top spot, Wikman took his political ombudsmanship to new levels during the 2008 campaign’s closing months. He donned a suit and was given a real pair of cufflinks to replace the paper clips he had been wearing, engaged in some remarkably effective PR for a technological Luddite, and actually stood onstage behind a dais with his name on it, debating on an equal footing with Hein and Bernardo and more than holding his own in a room full of people who had no idea he was on psychotropic medication, lived in a housing project and didn’t really know how he was going to get home that night. Having tirelessly accosted pedestrians in shopping malls and at public events, he amassed a symbolically significant 1,776 signatures on petitions, a feat he wrongly presumed would, even if many of them were thrown out by the nefarious powers in the Democratic party-controlled Board of Elections, mean that he would succeed in getting his name on the November ballot on his “1776 ‑ The Birthday Party” line.

Indeed, Wikman’s petitions were deemed enough of a threat to the power elite that a guy named Robert Porter, a Democratic Party foot soldier and former Kingston alderman, came out of the woodwork to file an objection to them. Porter was represented – some say recruited for the task as well – by arguably the most powerful attorney in Ulster County, Andrew Zweben, a guy who really deserves his own story as a ubiquitous string-puller.

The petitions were predictably turned down, and on Tuesday, September 23, 2008, Wikman appeared before state Supreme Court Justice Christopher C. Cahill in an appeal to overturn the election board’s decision. It was a valiant, Quixotic effort in the courtroom, as Wikman, representing himself quite eloquently and earning the grudging praise of his opponent, county attorney Josh Koplovitz, almost made the judge’s eyes water by throwing himself on the mercy of the court, telling the story of his lonely quest and of fighting through his dyslexia to get the error-ridden forms in on time. Cahill dried his eyes and threw out the appeal. Wikman countered by trying to mount what nearly everyone believed to be an equally hopeless write-in campaign.

A Wikman administration would either have been a marvel of bureaucratic efficiency or a logistical nightmare. Falling politically somewhere along the Libertarian axis (he’d been seen sporting “Ron Paul for President” buttons and stickers), the candidate produced a 19-point platform of promises stressing accountability, accessibility and complete governmental transparency, and committing to a preternaturally optimistic public appearance schedule that would have put a man half his age in the hospital. He said he’d hold “town hall” meetings in each of Ulster County’s 21 municipalities every month, as well as visit each town supervisor and mayor once a month – presumably not on his bicycle. He’d host anyone, any time, in his office, by appointment – assuming he’d ever actually be in his office. Somewhere in there, he said, he’d find time to videotape a weekly State of the County message. He promised to cut spending by improving employee productivity, and claimed he’d slash property taxes by 10 percent and veto any property tax increase sent to him by the legislature, or forfeit his own salary. On his wish list was a scheme to consolidate school districts across the region – not just one or two, mind you, but all 56 districts in a four-county area (Orange, Sullivan, Dutchess and Ulster) into one behemoth he said would be able to do the job for $30 million a year less. He envisioned a beefed-up tourism department that would be a moneymaker for the county to the tune of $3,600,000. It wasn’t clear where he got his numbers, but it was clear when looking into his deeply obsessive eyes that he believed in them.

Whether or not Allan Wikman’s political platform made sense, or whether his many almost alarmingly innovative ideas could actually work, is not the point of this story. What is most astounding is that this dirt-poor Hudson Valley cross between Randall McMurphy and Walter Mitty even got to the point at which he was tying up a state Supreme Court judge, two political bosses and a pair of high-powered attorneys for a few days, getting himself interviewed by regional public radio, and getting this tired old journalist jazzed about writing something for the first time in months.

He should not have been underestimated. Plus, there was one more thing …

The Hunt for Red October

October 2008 was probably as good a time as any to relate a salty yarn I’d been sitting on for a while, not really knowing whether to believe in its veracity, and not knowing whether Wikman would acquiesce to its ever seeing the light of day. But he gave me his permission – his blessing, even – and to his credit was willing to let the chips fall where they may. I published a version of this story in the October 2008 debut issue of the now mothballed Hudson Valley Chronic, a regional tabloid newspaper that was either 20 years ahead of or 20 years behind its time, depending on your point of view and maybe your generational identifier. When you’re done reading it, you may or may not have decided, as I did, that if you were an Ulster County registered voter in 2008, you’d have been writing in Allan Wikman’s name on the ballot for county executive on November 4 of that year.

The story:

“Biff, do you have a wetsuit? Do you know where I can get a boat?” Wikman asked me one October afternoon back in 2007, beneath the rotting edifice of the Uptown Kingston “Pike Plan” canopy.

I didn’t, but as I knew him to be a man of risk-infused action and a plotter of grandiose schemes, I was intrigued. It didn’t take long for me to figure out where he was going with this. He had found out that a band of Revolutionary War re-enactors would be wending their way up the Hudson to the annual “Burning of Kingston” celebration, and he was thinking about trying to stop them. He said he had tried to recruit Philip Riley, the artist who was arrested by the Coast Guard that August for attempting to pilot his replica of a 1776 submarine, the Turtle, through restricted waters up to the Queen Mary 2 for a gonzo photo shoot, but that hadn’t worked out.

“Stop. I don’t want to know any more,” I said, lying.

The weekend-long Burning of Kingston celebration repeats every two years with re-enactments of a couple of alleged skirmishes between the overmatched American defenders and boatloads of British troops landing at Kingston Point and in the Rondout. Fake cannons fire and fake soldiers run around on the beach and under the Route 9W bridge, shooting their muskets and lighting a controlled brushfire or two. Then everybody settles down and does their usual encampment ritual a few miles uphill from the river in Kingston’s Historic Stockade District, viewed by whatever tourists and locals happen to be around. Columns of British Redcoats march colorfully through the streets of Uptown. They go to historically accurate local taverns to drink and carouse. There is a Colonial ball, with uniformed officers and fancy ladies.

Wikman’s contention, after researching the 1777 calamity and talking to various historians including Kingston’s Ed Ford (RIP), was that there was no Colonial resistance to the British landing, which was supposed to be one of a series of “diversions” to lure Continental Army units southward away from Saratoga, where nobody knew that British Major General John Burgoyne had already surrendered to American Major General Horatio Gates. The interlopers simply came ashore and walked up the hill to the town’s center, setting fire to everything they saw. “There was no battle! It was an atrocity!” said Wikman, the outrage as fresh as if he were talking about September 11, 2001. “There was no immediate justification for the burning of the city. The British being pyromaniacs … they just burned the city because they were pissed at us and wanted to burn it. You might as well ‘celebrate’ the Holocaust!”

As the former editor of the Kingston Times newspaper, I had been aware of Wikman’s views on the Burning of Kingston event for some time. He had been railing against it for years in letters to the editor and in phone calls and e-mails to the mayor and other public officials, and had told me of his run-ins with people like Kingston’s Heritage Area Visitors Center director at the time, Katie Cook, whom he said called him “silly” and “a kook” for his haranguing of her to call the thing off.

Naturally no one listened, despite his going to extraordinary and even disturbing lengths to spread his message. “I got a list of all the veterans in Ulster County from Terry Breitenstein, head of the veterans’ service organization. He gave me a printout of all the veterans, and I called some. And I even called the commanders of the local VFW and the American Legion and so on, and they could care less. They could care less,” he moaned. “I read in the Daily Freeman that a man from Tillson had been elected state head of the VFW or the American Legion, and I couldn’t find his telephone number. So being a former executive recruiter, and accustomed to doing some detective work, I found out that the guy had a son who was a policeman in Poughkeepsie. So I called over there and left a message for him. And when I finally reached this idiot in Tillson, he read the riot act to me. He said, ‘What the fuck are you doing, calling my son about me, you know, blah blah blah blah blah blah blah,’ and I said, ‘Well, I apologize,’ and so on and so forth.”

He contrived a typically Wikmanesque PR campaign against the event, making up what to his mind were satirical 8½ by 11 posters that he placed on telephone poles around the city, presenting himself as a re-enactment producer and pretending he was looking for “small, Oriental men and women who had their pilot’s license and who could fly Zeros,” he said. “And then I was going to produce a celebration, a re-enactment of the defeat at the Alamo. And I wanted people to portray Davey Crockett and Sam Houston, and Mexican insurgents and so on and so forth, and also the Great Chicago Fire. And we were looking for somebody to portray Mrs. O’Leary and her cow. We would need firefighters for that, and old-time, old-fashioned fire wagons.”

The obscure, elliptical humor went way over the heads of Kingston residents, who wondered what the posters were trying to say. “Then I read, on the website of a British re-enactor, an itinerary of three vintage sailboats to be delivered over land to dockage at Verplanck, ‘from whence the crews will sail and/or row north over three days to Kingston Point beach,’ said Wikman, whose customary lack of restraint shifted into gear as he decided at that moment to mount an “attack,” either at the Chelsea Yacht Club in Wappinger on Wednesday, or at Marist on Thursday. He opted for Marist, and went on a reconnaissance mission on the preceding Saturday, first scouting the Highland shoreline in a borrowed car for a marina at which he could rent a boat, as he told the helpful locals, “to fish.”

Someone mentioned the North Poughkeepsie Boat Basin across the river as a likely boat rental facility, but that turned out not to be so.

The same day, Wikman drove across the river to the Marist campus, engaging the college’s security officer, an ex-cop, in deep conversation, telling him he was scouting the institution for his grandson, a crew oarsman. “We just stopped short of going and having a beer together; he was very helpful,” said Wikman, who then drove up to the marina, looking for a suitable boat to commandeer for his upcoming operation. The marina was closed, floodlit with security lights. A car approached – “neckers or something,” he said – and drove back out, as he kept to the shadows. The facility was primarily storage and summer dockage for power boats, and had no rental business, but the eagle-eyed and increasingly desperate conspirator wasn’t so easy to foil. He spotted an oversized inner tube, “a giant donut from one of those earth-moving vehicles,” sitting atop what he presumed to be a Sheriff’s patrol boat. “Inside there was enough room for a man, in a waterproof canvas trough,” said Wikman. “There were two handles on the outside, and a rope that was tied to one of the handles.”

That was enough for him. He resolved to continue with the plan, and would return on the night of the deed to retrieve the ungainly craft – despite reservations as to how he would propel or steer it in the river’s strong two-way current. “I said to myself, it’d be very difficult to navigate, but there’s no other boat.”

Up close and personal

Finally, D-Day arrived. In yet another borrowed vehicle, Wikman drove into Poughkeepsie from the north, picked up the big inner tube at the marina and lashed it to the top of the car.

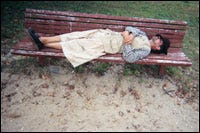

At about midnight, Wikman said, he parked in a lot near the athletic field at Marist, and approached the campsite to ensure the scene was set as he had hoped. He assumed the nonchalant demeanor of a tourist, not really considering that most visitors to Poughkeepsie are safely in their lodgings by midnight, nowhere near the dark, intermittently sex-crime-plagued riverfront. “I ventured, with my camera, through the tunnel out onto the riverside walk. As I approached, I saw in the distance four or five white field tents – Army tents – set up on the lawn just north of the Cornell boathouse. All occupants were apparently sailboat owners and the crew. There was one open-air sleeper – a guard – on the bench in front of the boathouse, right out in the open. It was as if he had a huge footlocker or a steamer trunk that he was sleeping on. He was rolled up, as well as I could see.”

“To test his wakeability, I guess,” said Wikman, he took “scads” of flash photos, including extreme close-ups of the sleeping guard and of the three boats moored at his feet. “In other words, I’m just a curious tourist with a camera,” he added wryly, chuckling at his cleverness and imagining a conversation that would have ensued had he been spotted: “You know, ‘I heard about this, and I’m intrigued – fascinated.’”

What he did not do was loosen the ties any of the three docked boats, an act he ruefully admits in hindsight would have increased the chances of his mission’s success.

He then drove south to the launch site and parked the car. Fearing the possibility of capture or losing personal effects in the river, he stripped down to a pair of shorts, sandals and a shirt, and stashed everything, including his ID and trademark eyeglasses. He hung the car keys on a fence, away from his own things and the car, to keep his friend from getting in trouble if he got caught. “Because I thought I might have to swim this whole thing, I then carried the bag with dry clothes to the shore, and left them on the bench in front of the Poughkeepsie Rowing Club building,” which is a few hundred yards south of the Cornell boathouse.

“Then I came back and I carried this huge donut down a few hundred yards to the water’s edge,” said Wikman. “Somehow I found a six-foot board, unwieldy as hell, and shoved off.”

Just then, as it sometimes does, the universe held its breath to watch what would happen next.

Miracles can happen

Experience paddling a canoe was no advantage, said Wikman. “I went around and around in circles. I went from one side and immediately it sent me one way and I went from the other side and it immediately spun me around the other way, and I got very frustrated. And there was a southward current going, too, so it made it very difficult to paddle.”

After an interminable struggle, Wikman maneuvered his way to the floating dock in front of the Poughkeepsie Rowing Club boathouse. He grabbed a tenuous hold of the striated aluminum decking, and had to slowly drag himself along 100 feet of dock to where he could grasp something of enough substance that he could lift himself off the craft without losing it to the tide. He was, in fact, only borrowing the donut for this little lark, and fully intended to return it.

“And then I spotted the rowboat.”

A rowboat with oars. For him to have happened ashore past midnight at the only spot on a five-mile stretch of river blessed with a one-man, human-powered watercraft requires a near Biblical stretch of the imagination to contemplate. Yet that, says Wikman, is just what happened.

Still, it was no picnic. The ordeal had just begun.

For one thing, sitting upside-down upon the stern seat was a large outboard motor, which was far too heavy for him to have lifted off the boat. And as if God were playing a game of Survivor with Wikman, the boat was laden with two feet of water.

There was no time to worry about such trivialities.

Wikman’s projected aura of tall, angular leanness was in fact an illusion borne upon good bone structure. At 6 feet tall and 210 pounds, he would have been a lot for a pair of 76-year-old triceps to move around on a swiftly moving fjord, even when not ensconced in a rowboat foundering with two feet of water and a dead engine, straining northward against an outgoing tide. “My thought was, what the hell?” said Wikman. “It’s either this, or I swim. There’s no other option. And I made an executive decision. I rowed vigorously against the tide, barely moving. The extra weight of the outboard and two feet of water was extremely tough. It took me 45 minutes to navigate just a couple of hundred yards, to just north of the floating docks and the three sailboats.”

With his legs and feet congealing in the icy water, the only image in his mind that pulled him through this ordeal, he recalled, was of rowing a warm waterbed through the mist. It worked.

Ignorant of whether or not he’d be spotted pulling up to the dock, Wikman forged ahead. “I rode the tide into the gap between the shore and the floating dock, and tied the bow rowboat line to the dock. The boat was pointing out into the river, held firm by the outgoing tide against the dock. In other words, ready to move. I crawled from the rowboat to the nearest sailboat, which was just a few feet away. The first sailboat had two moorings, one on the bow, and one on the stern. I detached both, and I tied the bow rope to the rowboat stern. It wasn’t a long distance; the sailboat and the rowboat were almost touching. The sleeping guard was just steps away, on a bench in front of the Cornell Boathouse. I crawled on my hands and knees to the second sailboat, which was right in back of the first, and attached the bow rope to the stern of the first sailboat.”

In the midst of creating this train of boats, a pair of headlights suddenly appeared along the shore. Wikman froze. The black SUV idled slowly past, pausing almost directly next to the sleeping sentry before moving on.

Wikman assumed it was the night watchman he’d spoken to earlier in the week. “He was only feet away from where I was. It was really dark, thank God. Apparently he didn’t see the rowboat there, or he figured oh, well, it’s just a boat. And boy, my heart was beating. I was right out on the dock, down on my hands and knees. My head was sticking up. … But I got down as low as I could – maybe I got down on my stomach, and just was motionless. And this guy stopped, for maybe a minute, and then he drove on.”

Wikman didn’t have any idea, but when he related this part of his story, my own heart skipped a beat. Because what no one realized until that point was that the driver of that black SUV was most likely me. I had been suspicious that Wikman was going to do something that night, and I had wanted to witness it. In the pitch black, I had seen only what was in my headlight beams. I had no point of reference and had no idea what I was looking for. I prowled around, parked and investigated the wrong boathouse further south, and left, thinking nothing at all had happened.

To think I inadvertently nearly scotched Wikman’s mission …

A god among mortals

Anyway, here we are at the point so heavy-handedly foreshadowed at the outset of this odyssey. The rest is also the stuff of legend, but can be dealt with in a sentence or three. For instance, after being discovered, how on Earth did Wikman escape? The Tories must have had him dead to rights, with him huffing and puffing out there pulling what must have been at least three-quarters of a ton of boat, motor, ice water and ancient homo sapiens. After hauling the boat (or boats; Wikman insists he had two of the re-enactors’ craft in tow, in conflict with an earnest blogger’s blow-by blow report) around a 90-degree angle from the tee-shaped dock into the outgoing tide to get going, he was probably blown southward like an Indonesian bathtub in a tsunami. If the tide was that strong, how did he get back to shore?

Indeed, our hero was pretty far south when he encountered land somewhere in a post-industrial wasteland, clambered up onto the concrete levee and hurtled through the briar-infested underbrush only to find himself trapped in an abandoned factory property surrounded by an un-scalable Cyclone fence, running like an elderly Polish refugee as sirens and flashing lights cut off every avenue of escape.

Yet again, he muddled through, and was able to get himself and his friend’s car home in one piece.

Perhaps spurred on by the taste of blood (all of it his own), Wikman felt compelled to attend the Burning of Kingston festivities the very next day, sidling up to the same crew he’d nearly marooned the night before, asking questions like, “So how’s it going? Everything OK on your trip?" and even considering another run at the boats at Kingston Point. He then returned to the abandoned factory property a few days later, looking for the rowboat he had scuttled there in an attempt to retrieve and return it, but managed to slip on some concrete and crack his head open. After stumbling to the emergency room to get his head swaddled like a 6-foot-tall Q-Tip, he stopped by the Poughkeepsie Police Department to pick up a copy of the incident report.

It's a small wonder they never put two and two together.

Allan Wikman in my ink-addled mind, as a result of all of the above, had approached a modicum of godhood. I vowed at the time to at the very least vote for him, but frankly, county executive would have been a comedown. As with Don Quixote and other more historically real epic strugglers, the mere act of beholding a Wikman figure and contemplating his impossible life makes one a better person and the world an almost exponentially better place. He did not come close to winning, or even placing in the November 4 election to become Ulster County's first executive. Mike Hein won, and was able after a few years to parlay that into a lucrative position in former Governor Andrew Cuomo’s administration. Meanwhile, spies told me that Wikman had been lurking around the polls at Sophie Finn Elementary School that not-so-fateful Election Tuesday, presumably trying to check for any telltale clicking of the miniature slider in the window above column 8 on the ballot, which would have meant someone was at least trying to vote for him.

As I promised, I did cast my vote for the star-crossed candidate, who continued to befuddle and amaze all who crossed his path … at least until I lost track of him while abandoning Kingston, Ulster County, and eventually, any further futile attempts at independent-minded journalism.

Unlike me though, the irrepressible, possibly insane Wikman didn’t lose his knack for being a pain in the system’s ass, seemingly everywhere at once. As I was wrapping up writing the above screed, it came to light that he had been present in a tent at the Rosendale Street Festival when he saw -- and took a grainy photo of -- former Democratic U.S. Congressman Maurice Hinchey (RIP) allegedly taking a swing at an NRA supporter who had apparently been baiting him. Wikman told me he was flabbergasted as he witnessed the dustup, in which old Fightin' Mo -- again, allegedly -- bopped Catskill Regional Friends of the National Rifle Association chairman Paul Lendvay on the top of his head.

So once again, just by "stopping by" at the NRA hospitality tent as Hinchey -- ironically an opponent of gun control -- got goaded into losing it by a fellow gun-lover, our Walter Mitty was in the middle of a big story, this time in the position of an unfriendly witness against a guy he claimed not to have much respect for.

Not long after that, Wikman was again plotting. The campaign trail is a lonely place, especially if you’re on Social Security, dyslexic, unaffiliated with any party, and the powers that be are plotting to keep you off the ballot. But that didn’t stop Allan Wikman. In 2010, at the age of 78, he began another run for Ulster County’s top political office, which was the last time I caught up with him. As an example of the classic political “gadfly” — that species of hectoring nudge that have plagued local municipal boards and legislatures since time immemorial — Wikman was, to me, a difficult but ultimately worthwhile subject. When more savvy newspersons than I would spy him loping down the street toward them, they would usually run into the nearest coffee shop and hide until he disappeared. Politicians, lawyers and people known to carry around large sums of cash would usually do the same. But I, perhaps because Wikman was infused with the sort of politically idealistic fighting spirit I’d like to see take root in this region’s listless, beaten electorate, liked to give him his inches and a small soapbox from time to time … even if it had little or no real effect.

Through much of his tenure as a candidate and gadfly, Wikman never missed a monthly session of the Ulster County Legislature, monitoring and occasionally weighing in on the proceedings from an unconventional but grudgingly tolerated perch on a windowsill at the back of the room. He was again in the news as the 2009 Burning of Kingston event was marred by what he insisted to police was a “copycat” shanghai-ing and intentional grounding at Kingston Point of another, even bigger boat — perhaps, he claimed, by a mysterious female schoolteacher who had been “inspired” by his well-publicized (in the Hudson Valley Chronic, at least) jihad of two years earlier. I stayed away from that one, except to make a quote or two in a competing paper and to compare notes with a well-known local blogger from another organization. Wikman was not charged, although he remained under permanent suspicion.

Sit-down strike

The final act of Wikman’s long battle had its genesis when he attempted to sit on his customary windowsill at the year’s first meeting of a new, suddenly Republican-controlled Ulster County Legislature on January 6, 2010. The fledgling GOP majority, headed by Chairman Fred Wadnola, at the time a beloved restaurant owner and retired former supervisor of the Town of Ulster, was in no mood to have Wikman looking over its legislators’ shoulders and taking verbal potshots, as he had done during the previous Democratic-controlled legislature led by the more tolerant Dave Donaldson. Signs had been posted on the walls announcing the new policy that no one would be allowed to sit in the back of the room. Yet there Wikman was, all dyslexic 210 pounds of him, pretending not to notice but fully realizing that the jig was probably up and no doubt salivating over the constitutional battle that was about to ensue on his behalf.

After getting the word from Wadnola, the county sheriff himself, Paul Van Blarcum, along with Undersheriff Frank Faluotico and a couple of security guards, approached Wikman and asked him a few times to please move. According to court testimony Wikman didn’t budge, and when they subsequently lost patience and put their hands on him he dropped to the floor in an ungainly ’60s-style heap of nonviolent resistance, saying: “you’ll have to carry me out.” The four lawmen, one on each limb, physically hustled their cumbersome load from the packed room as he allegedly spouted to the gallery: “Look what they’re doing! They’re violating my constitutional rights!”

Wikman was taken to the Ulster County Law Enforcement Center and charged with disorderly conduct, a charge that lingered unnoticed in the air for four months until it finally stuck on Monday, May 3, 2010, when Kingston City Court Judge Lawrence Ball pronounced him guilty and sentenced him to 15 days in jail with a conditional discharge, provided he refrain from sitting on the legislature windowsill or creating any similar disturbance for a year. Presumably this would include getting caught stealing another Revolutionary War re-enactor’s boat, but the next Burning of Kingston was still a year and a half in the future.

The trial was entertaining to the four uninvolved-but-still-interested parties in attendance, who included myself, another journalist with too much time on her hands, and a nice couple from Rhinebeck who were friends of Wikman. The most interesting thing, to me, was that once again Wikman brought against himself an odd assortment of players whose associations and interplay pique the curiosity of someone seeking to understand the way true power works.

The lawyers and witnesses outnumbered the onlookers. Wadnola was the star witness for the prosecution, which was handled by Ulster County Assistant D.A. Cindy Chavkin. He brought his own representation, in the form of attorney David Van Benschoten, whom I remembered well from his vigorous but ultimately fruitless defense of the American Candle Company, a.k.a. Clearly Tech, against efforts by the Town of Saugerties to shut down what was alleged to be a toxin-spewing, worker-abusing sweatshop, for assorted building and safety code violations among a long list of other indignities. The empty, rusting hulk of that factory, the ground beneath it brimming with toxic chemicals dating from its chip manufacturing heyday in the hands of Philips Electronics North America Corporation, still stands in the way of meaningful development in the Kings Highway corridor.

The candle factory, when it was debuted in the summer of 2000, was owned by Seagrams/Vivendi heir Michael Bronfman, and was a pet project of Charles Gargano, chairman of the state’s Empire State Development agency, who came for the ribbon cutting with his pal, former Gov. George Pataki, promising the usual 400 or so high-paying jobs. After a few months, the only jobs were for five-foot-tall Andean wage slaves, bused in from the Bronx every day to stand on crates, and allegedly working two or three to a Social Security number.

With my customary relentlessness at the time, I did a series of stories in the Saugerties Times that helped get the thing shut down so people in the neighborhood could breathe better (the sickly, probably cancer-causing candle fumes were making them sick). When I asked him questions about his clients, Van Benschoten looked at me like he wanted his eyes to turn into lasers. I developed a working relationship with the town building inspector, a stand-up guy if there ever was one. I followed the buses, obtained photos of the work conditions, and interviewed a former accounting employee as to the alleged employment fraud. None of that evidence was ever followed up on by local or state authorities.

But I digress, as usual. The point is, it was nice seeing Mr. Benschoten representing someone more deserving and reputable.

Also in the witness box for the prosecution during the proceedings were Faluotico and the legislature’s senior security officer, David Mead, who testified in uniform. Both men basically supported Wadnola’s testimony, that Wikman was told sitting on the windowsill would no longer be allowed, was asked multiple times to get off it, refused multiple times, and slumped to the floor in an uncooperative heap when they and their boss and co-worker attempted to physically escort him out.

Wikman’s court-appointed defense attorney, Will Meyers, kept trying to paint the picture of a man sitting where he always does and minding his own business, who had no intent to disturb anything but just wanted to be left where he was. He described the window seat as the only place in the legislature room that Wikman, who is aurally challenged, could hear anything. He found one witness, Rev. Julius Collings, who would testify that Wikman was a harmless old dude sitting where he always does, and didn’t disturb anyone. “It didn’t make me feel good that it would happen; that anybody would be taken out in that manner,” testified Collings when asked a leading question by Meyers as to how he “felt” about what he saw that day.

None of this swayed Judge Ball, who really didn’t have a choice. You don’t get anywhere in life siding with 78-year-old dyslexic, hard-of-hearing malcontents against the county sheriff and the chairman of the legislature. But he did stand firm against the prosecution’s attempt to impose a fine and make Wikman serve five days of community service (which I would have paid to see). “I agree that this seems to have been an act of civil disobedience,” allowed the judge, perhaps inadvertently setting the grounds for a possible appeal (which Wikman vowed up and down to make, despite the fact that he had no money).

Wikman also vowed to run again for county executive, a doomed quest that would surely have engendered another story or two.

At any rate, somewhere in there the ball stopped rolling, first for me and the under-performing Hudson Valley Chronic, and then for the mythical Allan Wikman, who dropped out of sight and earshot for 10 years, and reportedly passed on in 2020, sadly and without further comment or fanfare. This piece can be considered as an epitaph of sorts, as well as a cautionary tale to myself to avoid giving up. RIP, Allan Wikman, and thanks for the memories.